As the Trump administration identified pro-Palestinian academics to target for deportation, it relied heavily on an anonymously-run pro-Israel website that has been criticized for doxxing, according to newly unsealed court documents and testimony at an ongoing trial.

To support President Donald Trump’s deportation drive, the Department of Homeland Security assembled a “tiger team” of intelligence analysts who built dossiers on about 100 foreign students and scholars engaged in pro-Palestinian activity, the records show.

More than 75 of those people were identified by the shadowy website Canary Mission, according to deposition testimony unveiled this week in a case challenging the Trump administration’s targeting of pro-Palestinian scholars.

The federal judge currently overseeing a trial in the case unsealed the deposition transcripts, which contain hundreds of pages of sworn testimony by administration officials about the campus deportation effort. Some of the details in the transcripts were fleshed out in open court Wednesday as administration officials began to be called to the witness stand.

In response to a query from POLITICO, Canary Mission said in a statement Wednesday that it “had no contact with this administration or the previous administration.”

White House spokespeople did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Immigration lawyers and pro-Palestinian activists have previously suspected that immigration authorities were plucking the names of academics from the Canary Mission site and seeking to revoke their visas with little independent research. But the depositions reveal for the first time how broadly Trump officials relied on the website. Testifying at the trial Wednesday, Homeland Security official Peter Hatch acknowledged the site’s significance to the Trump administration effort, but said any information taken from the site was independently verified.

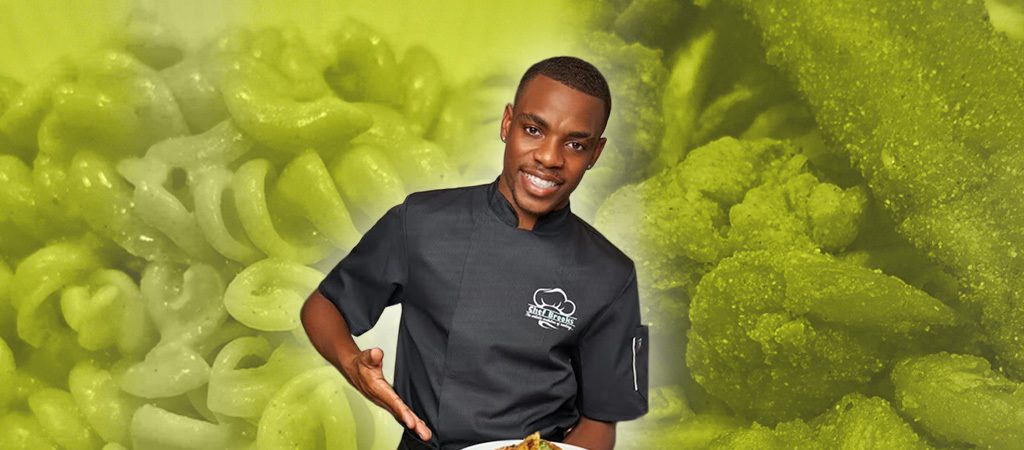

Canary Mission says its goal is to expose anti-Israel and antisemitic sentiment on college campuses. It posts photos and social media profiles of pro-Palestinian academics and logs their protest activities.

Critics accuse the group of McCarthy-like tactics by painting pro-Palestinian activists as antisemitic based on thin or irrelevant evidence. Canary Mission has not revealed its funders or details of who operates it.

“We document individuals and groups that promote hatred of the USA, Israel and Jews. We investigate hatred across the political spectrum, including the far-right, far-left and anti-Israel activists,” the group said.

The unsealed court records also reveal for the first time how deeply involved the Trump White House — in particular top Trump aide Stephen Miller — was in the effort to revoke the visas of pro-Palestinian academics studying and teaching at American colleges.

The acting chief of the State Department’s Bureau of Consular Affairs, John Armstrong, testified that he’d had “at least a dozen” conversations with White House officials about the student deportation drive and that Miller was on interagency conference calls related to the issue “at one point at least weekly.”

According to Armstrong, the conference calls with Miller lasted about 15 minutes to an hour and involved other officials from the Homeland Security Council, the State Department and Homeland Security Department.

The extent of the White House’s involvement in singling out particular students remains unclear because the White House asserted executive privilege to conceal the details of Miller’s exchanges with agency officials.

Still, the revelations shed new light on the Trump administration’s aggressive efforts to target, detain and deport foreign academics who are living and working in the country legally. For months, Secretary of State Marco Rubio appeared to be the face of those efforts: He invoked a rarely used provision of immigration law to try to deport targeted scholars — including Mahmoud Khalil and Rumesya Ozturk — by declaring their presence in the U.S. in conflict with American foreign policy interests.

Admin officials reveal new details

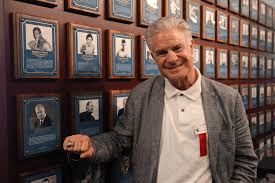

The detailed testimony about the administration’s controversial bid to deport pro-Palestinian academics emerged in more than 1,000 pages of documents and deposition transcripts made public as the trial challenging the policy began in federal court in Boston this week. U.S. District Judge William Young is presiding over the trial and will decide whether the Trump administration violated the First Amendment by targeting academics based on their speech and political views.

The foreign-born academics were living and studying at American universities legally, either on student visas or green cards. But the administration has tried to revoke their legal status and force them to leave the country. Courts so far have intervened to prevent the immediate deportations of Khalil, Ozturk and others.

Hatch offered new insight into the roles of outside groups in targeting academics.

Called as a witness Wednesday at the ongoing trial, Hatch confirmed the key role of Canary Mission in the agency’s intelligence work related to deportations.

“Many of the names or even most of the names came from that website, but we were getting names and leads from many different websites,” said Hatch, assistant director for intelligence at Homeland Security Investigations. “We received information on the same protesters from multiple sources, but Canary Mission was the most inclusive. The lists came in from all different directions.”

Hatch added that he believed he was told verbally that his team needed to review the Canary Mission website and that it contained reports on more than 5,000 people. “Which shows why we needed a tiger team,” the Homeland Security official said. “A normal unit or section or group of analysts operating in a normal organizational construct couldn’t handle that workload.”

Analysts assigned to a “counterterrorism intelligence” unit, among others, were re-assigned to the “tiger team,” Hatch said.

Hatch also insisted that any information his analysts obtained from the Canary Mission site had to be corroborated before being included in official reports.

“Canary Mission is not a part of the U.S. government,” he said. “It is not information that we would take as an authoritative source. We don’t work with the individuals who create the website. I don’t know who creates the website.”

In his deposition, Hatch said “more than 75 percent” of the names his “tiger team” prepared reports on came from Canary Mission, and he believed others came from from Betar US, a group that uses the slogan “Jews fight back” and profiles pro-Palestinian activists on its website.

In February, the Anti-Defamation League added Betar to a list of extremist groups, alleging that the organization “openly embraces Islamophobia and harasses Muslims online and in person.”

Betar did not respond to a request for comment. However, within days of Trump’s return to the White House in January, Betar announced on X and in comments to news outlets that it had provided a “deport list” to Trump administration officials.

The trial stems from a lawsuit filed in March by the American Association of University Professors and the Middle East Studies Association, claiming that the “ideological deportation” policy violates the First Amendment.

Administration officials called to give sworn depositions in the lead-up to the trial struggled to give precise definitions of what sorts of advocacy or activism would be deemed antisemitism or support for Hamas, which the U.S. has designated as a terrorist group. Both grounds were primary justifications for the deportation drive and parallel efforts to deny visas to foreigners seeking to study or continue their studies in the U.S.

Armstrong said in his deposition that a frequent chant at pro-Palestinian rallies, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” could be regarded as disqualifying for a U.S. visa because it could be viewed as calling for the destruction of Israel.

“It could be in my opinion, because by definition, it means the elimination of Israel and the Israeli people,” the State Department official said.

Armstrong went on to say that a call for institutional divestment from Israel, an arms embargo against Israel or an end to military aid to Israel could all be problematic. He added that calling the country an “apartheid state” would “probably” be considered anti-Israel activity.

However, Armstrong said, calling for a ceasefire in Gaza would not be held against a visa applicant.

“The president has called for a ceasefire. So no,” said Armstrong, who is scheduled to testify at the trial on Friday.

Asked to explain what sort of anti-Americanism could result in denial of a visa under new Trump policies, Armstrong replied: “It would be a blanket condemnation: All Americans are fat and evil. It would not be: I hate hot dogs.”

A monthslong deportation effort

The new details from Trump administration officials also show many aspects of the policy remain a work in progress, nearly six months after Trump returned to office promising a crackdown on foreign students he regards as troublemakers.

Armstrong said he was unaware of any instructions given to consular staff about how to determine if particular speech is antisemitic.

And the State Department official who oversees visa issuance, Stuart Wilson, was asked during his deposition two weeks ago whether his office has “been given any guidance about whether a student’s activism is consistent with their student visa.”

“It’s still under discussion,” Wilson replied.

Early reports about the student deportation drive cast Rubio as the key player in the effort and left unclear how officials at the State and Homeland Security Departments were deciding which of the roughly 1.1 million foreign students in the U.S. to zero in on for potential expulsion.

Rubio has suggested a higher figure for the total number of student visas revoked than those discussed in the newly released depositions. During a March press conference, he said the number could be over 300. Rubio has also reinforced the idea that he is pivotal to the project.

“Every time I find one of these lunatics, I take away their visa,” Rubio said. “Might be more than 300 at this point. Might be more. We do it every day.”

However, administration officials said government discussions about revocations of visas for academics are sometimes grouped into broader discussions about revoking visas for others.

At the trial this week before Young, a Reagan appointee, several professors testified about the chilling effect the administration’s crackdown has had.

A Harvard philosophy professor who is a German citizen, Bernhard Nickel, testified Tuesday that due to fear instilled by the high-profile arrests of pro-Palestinian academics, he stopped attending protests, signing public letters and traveling internationally.

“I actually just decided on a blanket policy that I would keep my head down completely,” Nickel said.

Nickel said he defended some student activists at Harvard against university discipline. But, on the witness stand, he also expressed concern that aspects of the pro-Palestinian protests had sometimes veered into antisemitism, particularly one in Harvard Yard that featured a crude caricature of Harvard President Alan Garber, who is Jewish.

“That’s just a very well known antisemitic trope,” he said.

Young, who is hearing the case without a jury, shot down one aspect of the case plaintiffs hoped to present: evidence that American-citizen academics’ right to hear speech by their non-citizen colleagues was being impaired by Trump’s deportation policies.

Young also raised doubts Wednesday about whether the suit brought by the academic groups can or does challenge the rarely invoked law protecting foreign-policy interests that Rubio used to set in motion many of the student deportations.

“I don’t know that your clients have standing to challenge it, as the statute has never been used against any of them,” the judge said.